You know me, readers. I love a book where someone is talking about the consistent patterns and behaviours that show up in systems, regardless of the details of the system. Here we have a scintillating read about How Big Things Get Done, and I’m right in there, gobbling up all the logistical observations.

Of course, another Big Thing is getting done this week, in America. I find the whole thing acutely painful to observe. I could have chosen Rebecca Solnit for this moment, or Valerie Kaur, or Ijeoma Iluo, but since I and my audience are mostly not in the position to vote or donate, even though the outcome will affect us too, I offer instead a small salve against the disempowering firehose of American election content.

We can, if we want, choose to think about stuff like what even is a “project”? 🤔 And how do projects “get done”? (You are WELCOME, readers.)

Once again, I bring you a book when I am only a quarter of the way into it. This is a gift to you, readers, since it’s easier to report a thing or two from the beginning of the book than the full impression I get from the whole thing. (By the way, I finished Wifedom. It’s excellent. A+++ highly recommend. Would the whole newsletter be reflections in this form if I reported after I’d finished? Probably.)

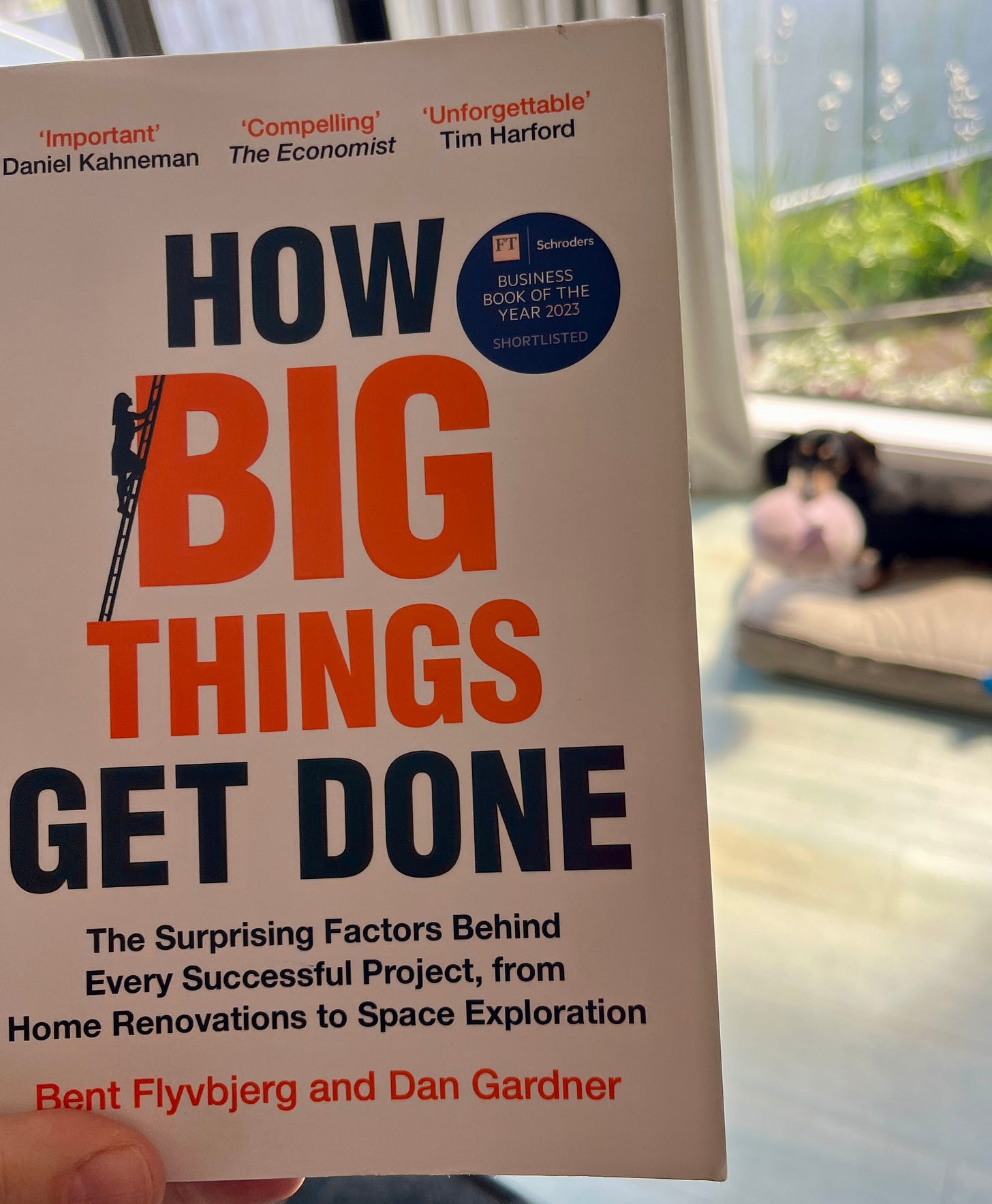

Bent Flyvbjerg is an academic and consultant on the topic of mega projects, and also something called an “economic geographer”. His career has had him working on countless individual mega projects as well as studying their successes, failures and behaviour in the aggregate. We love such an expert, don’t we folks?

His book, written with journalist Dan Gardner, assembles what Flyvbjerg has observed as probabilistic laws that determine the success or failure of mega projects. He is quick to note that “mega” is relative - a $1 billion bridge project is “mega” to a government, but a home renovation is “mega” to an individual.

And what counts as success in this realm? Projects that are completed on time, within budget, and delivering the benefits they sought to deliver (or better, on all three).

A whopping 0.5% of projects studied in Flyvbjerg’s joint research with McKinsey were successful in these terms. This research considered a database collecting data related to mega projects across the world and across industries, some 16,000 projects at the time of writing. 0.5%! And the patterns that Flyvbjerg et al observed within that data showed consistent patterns.

Obviously, there are many patterns, and many features, many of them related to the psychology of individual humans and the political contexts of their projects. I can’t offer you them all; I haven’t even read them all yet.

The biggest one though, and the one to kick off with if you are on the precipice of a project yourself, is this one:

“Think slow. Act fast.”

His point? Most of the overruns and extensions and mistakes happen once action starts. In planning, you have the chance to probe and question and re-imagine without much cost, and with the benefit of then informing a plan that can be acted on quickly.

But what does it mean to plan?

“Projects routinely start with answers, not questions.

David and Deborah’s project started with “renovate the kitchen.” That’s an answer, not a question. As so often happens with projects, the goal of the project seemed obvious, a given. The only question was when to go ahead with the project, and once that was decided, it was time to get into detailed planning. The failure to ask questions about the goal of the project was the root cause of its failure.”

I love this so much, partly because it is a HUGE part of my work as a coach, and because it is so energising to come at projects, or plans of any kind, from their underlying purpose. Yet it isn’t most people’s default way in.

“Projects are not goals in themselves. Projects are how goals are achieved.”

When I set out to redesign the food storage layout of my pantry and kitchen, I asked myself, “why do I need to do this?” The answer? “I want to support ease in making far more interesting and diverse food, plus I want less clutter.” (In fact I wanted less clutter because that would support ease in making more interesting and diverse food.)

That’s a very specific reason! It is not, “to improve my aesthetic experience”, or “to improve accessibility”, although that was part of it, or “to feel like I match what ‘good kitchens’ look like on Instagram”. If any of those had been my goal, my actions would have been different.

Once I had my why, I determined a collection of principles to guide decision-making within the project. Things like, “follow actual behaviour”, and “make access to spices and accoutrements very easy and very visual”, and “support ease of use of unfamiliar ingredients”. That last one means having little post-its showing flavour/ingredient clusters I’ve enjoyed, and also cooking ingredients for grains I’m not yet fluent in.

And, there were ancillary goals, like “use the storage options I already own”, since a project has more values than the primary goal it’s aiming at.

Once I had my principles, and my why, and all my existing storage options sitting on my bench, I was able to remove everything from the pantry, and put it back in its new places, with relative ease. This is important for me, where my scarce resource is not time, or in this case money (because I wasn’t spending anything) but CAPACITY. The lifting and carrying and organising bit needed to be efficient.

And then, after an hour’s planning, and an hour’s doing, it was all done! A project I had thought would be a Big Goal for the month! All done and ready to go.

I feel such a thrill approaching projects this way, something I’ve long done but still like to read about. It’s probably why I love coaching work so much.

It seems so simple to orient from the purpose you’re trying to achieve, yet so often it can get lost in the course of the project, whether at the level of international coalitions or individual households.

It’s even more likely to get lost if the participants never articulated the real purpose to begin with.

What an opportunity to experience action, projects and pursuits in much more human, not to mention effective, ways. 😌

May you know your projects to be a means to achieving your purposes, not the purposes themselves.

May the big project of democracy hold up to the next few weeks.

May I now enjoy doing all that Greek cooking I’ve wanted to do forever.

Until next time,

Katie

Thanks for reading The Living Library, where we grapple with complexity and humanity and all the good stuff.

I am a coach, consultant and educator, working people who are highly self-led and who care deeply, including highly sensitive and gifted adults. I work with clients on whatever they need support with, from high sensitivity/giftedness itself, to crossroads decisions, to self actualisation and transformative change, to creative development, to leadership (and all the interconnected everything else inbetween).

If you like what you read in here, you may enjoy working with me. 😌 You can learn more in this post here:

Work with me 1:1

A little break from our usual fare, readers, as I let you know a little about my coaching and consulting practice.

I do appreciate those who use words as windows. The simple shift from 'the project is not the purpose' is like pulling back a huge heavy slider and letting in all that possibility. Another I have loved is 'to design is to redesign' and that fits with the 'slow' for thinking and planning. This really is a living library! Thank you.

That is a beautiful pantry! Please pop by and help with mine. And the circus that is the rest of our apartment…