Late last century, neoliberal political theory took over New Zealand’s politics. Everything should be run like businesses (more on that later), and with less regulation.

Throughout the 1990s, while these theories were being applied to health reforms that resulted in, among other things, patient deaths, my Dad worked at Christchurch Hospital.

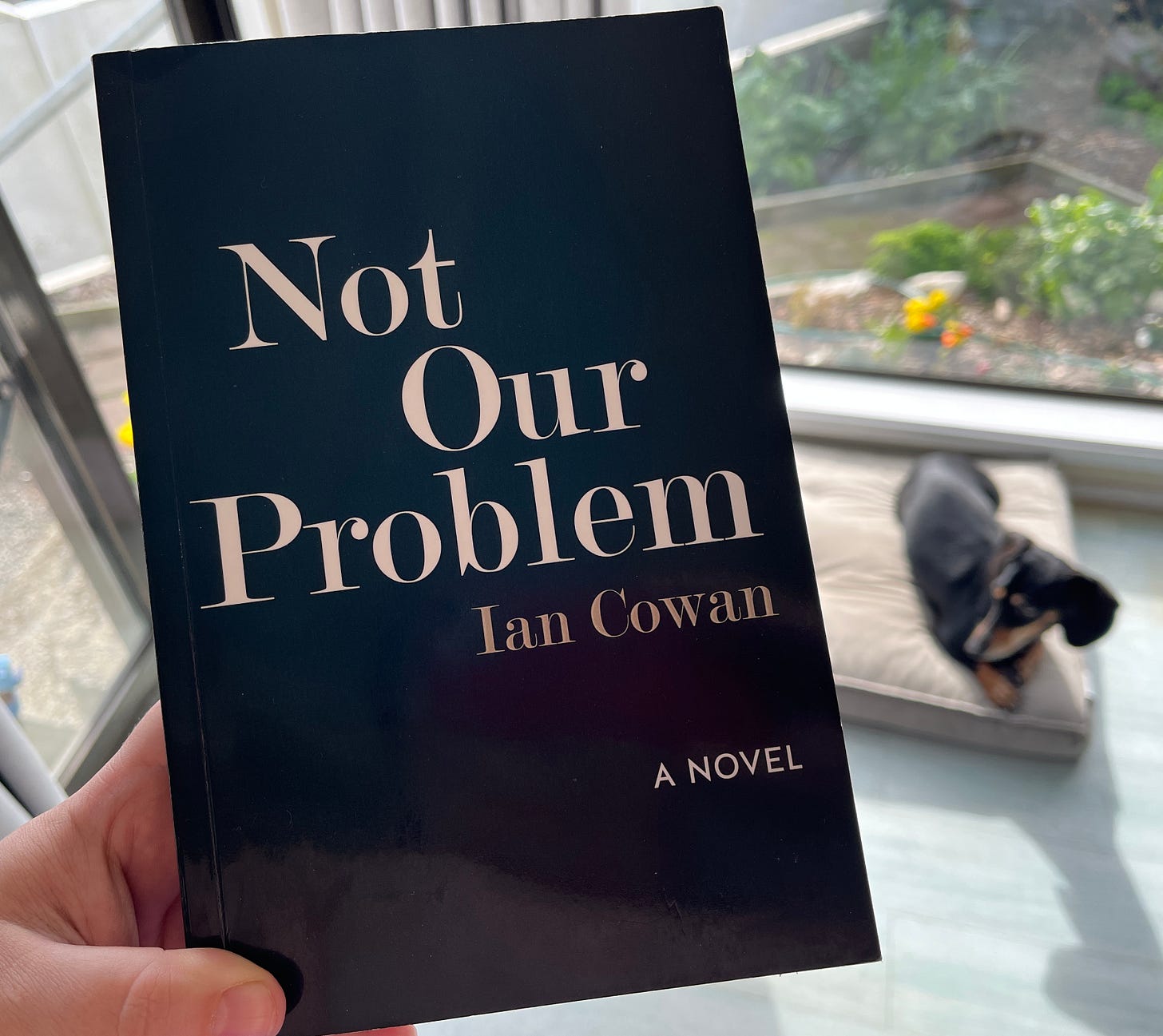

In 2015 he published a fictionalised account of the reality of those reforms, complete with a bleak set of footnotes that showed how the substance of the book was not really fiction. Each of its biggest and worst events had grounding in real life events. (He brought the receipts.)

This week, a mere nine years later, and knowing how the current New Zealand government is behaving in all the same ways as the government of the nineties (except this time with more contempt for democracy and Te Tiriti), I read this book.

(Let us skip past that time gap where someone fails to read her dad’s novel for nine years. That is all about a weird aversion to fiction that developed after high school, and the bigger story of how a rigid self-concept (“I can’t read fiction”) can soften and change (“I can sometimes read fiction if a family member wrote it”). A true thing I said this week: “Wow, when you read fiction, it’s like you get a whole different perspective from inside the person.” 🤦🏼♀️ But this is not today’s focus.)

At the same time this week I have been re-reading Donella Meadows’ book on the nature of complex adaptive systems: their behaviour, their foibles, and the realities of how the whole world works. It has brought me incredible joy, partly because I still don’t fully get it and Donella assures me no-one can fully get it.

But, it’s a tender time to revisit how complex and interdependent reality is, under a government that seems to have contempt for that reality. (Here’s a quick catalogue of what it is doing, and how quickly, and how undemocratically, thanks to Emily Writes. It is acutely painful to read.)

Truly, I find it unbearable to live under this government, and governments like it, let alone alongside everything going on elsewhere in the world. I donate and make submissions and sign petitions, but it remains unbearable.

And so it was a strange salve to read Dad’s book right at this moment. To read how dry, number-y, weasel words policy plays out in human scale. And to read what the individual, who has limited power to stop political forces like these on their own, does (alongside others) to meet unbearable reality.

I say that both in terms of the main character, whose actions I won’t spoil, but also Dad himself, writing this book to record the reality of what happened (not letting it get lost to history), and as a red flag of warning against it all happening again in thirty years. (Chris, baby, Dad will send you a copy if you want.)

'“I disagree,” said King. “To people with the right skills, running a hospital is no different than running an aluminium smelter.”’

[In the footnotes: “I heard a manager shout this in a noisy meeting like the one described; I don’t know his name and I never saw him again but that moment was the genesis of Not Our Problem.]

I find it unbearable to live under a government that thinks a business is the same as a country, when a business is a relatively simple complex system, with far less at stake and far less need for resilience or long term endurance than a country. It is a child-like conception of reality, and I don’t understand how anyone takes it seriously.

I also find it unbearable to watch in real time as the country’s long term resourcing in so many domains gets stripped, in service of wealth creation for a few people, and apparently with no mind to the consequences of what’s being lost.

But this is not a news newsletter. (Others do those very well; I am not your girl for that.) This is a newsletter about the complexity of things, the humanity of things, and the role of the individual within all of that. It is sometimes about trees and jigs, and sometimes about how people have borne unbearable things.

In this case it’s about how people care for each other amidst top-down harms, and how art and activism take care of the bigger systems.

May you play whatever role you can in resourcing the humanity and resilience of our systems.1

May you make the art you are called to make; it’s a vital part of the system.

May you read Dad’s book.2

Until next time

(I’ll talk about joy or something, I promise.)

Katie

A good first step would be to subscribe and donate to ActionStation, since they tell us all what needs doing and when, and action in numbers is the way to go.

Love the way you weave seemingly disparate and big topics into a single post. Thank you.